Ishkashim – Bodurbekov Family

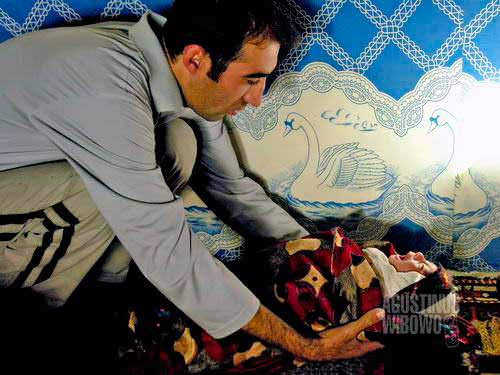

Alisher (a.k.a Muhammad Bodurbekov) with his cousin

“Now you are not guest anymore. You are part of our family. Welcome!”

– Muhammad Bodurbekov

Since the first minute I arrived in Ishkashim, I was impressed by the hospitality of the people in the Wakhan Valley. I was invited by Muhammad Bodurbekov, 29, to his house in the village. Muhammad, alias Alisher, worked in Dushanbe in Aga Khan’s NGO, MSDSP. He had classes in Khorog and he then had chance to see his family in Ishkashim. He spent a month in the UK for his higher education, and he still maintained his British accent. Alisher was an educated professional and he had so many things to discuss. So before starting, let’s sit on the ‘kurpacha’, the guest welcome matress, which Alisher laid between the pillars of Ali and Muhammad. Sitting on the kurpacha symbolized the acceptance of the welcome gesture from the host.

In this house there were Alisher’s father, mother, sister, and some nephews and nieces. Alisher sister was married already but she was staying in her parents’ house. She was married to a man from Shegnon and according to the Shegnon tradition, the first child should be born in the mother’s parents’ house. Alisher’s other sister was in Moscow and she let her parents to grow her son and daugher. Alisher’s mother still work as a primary school’s headmistress and his father was enjoying pension of 93 Somoni per month. Alisher had a twin sister, and now was in local hospital due to last week’s car accident.

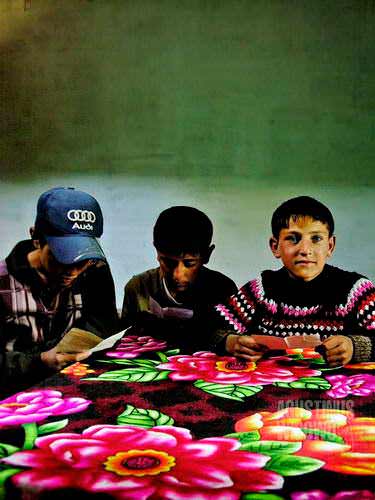

Ishkashim boys inside their traditional Pamiri house.

Alisher’s parents’ house was a modernized version of traditional Pamiri house, with the main characteristic of the five pillars. This traditional house dated back far before the arrival of Islam, but then each symbol was linked to Islam. The hall was very big, much bigger than those I used to see in Pakistan and Afghanistan sides. It was a very bright room with very big skulight hole, where the sunlight came to illuminate all of the corners of the room. It had also huge glass window, something that was less commonly used in Pakistan and Afghanistan. The wall was covered by traditional designed textile, and as later I found in all Ismaili houses in this valley, this room also had a photo of the Highness Aga Khan.

Alisher’s family didnt sleep in this room. I bet this room, considering its wide space, was used in summer. In winter they used a smaller, but much warmer room nearby. “This is a common room in all of Tajikistan. All houses in Tajikistan have this kind of room. But that ‘Pamiri house’ is unique only in Badakhshan’s culture,” said Alisher. This smaller room had also a photo of Aga Khan on the wall. Alisher’s mother cooked and made the bread here. With all of the modernization the Soviet introduced, thandoor (traditional mud stove to make bread, which is a hole on ground) is no longer used here. Instead gas stove can be found here, making food was much easier. Alisher’s sister’s little baby was sleeping in the craddle (guwara). He was only one and half month, and yet had a name. Manoucher, Alisher’s 7 year old nephew, kept swinging the craddle to kept the baby cousin sleep soundlessly.

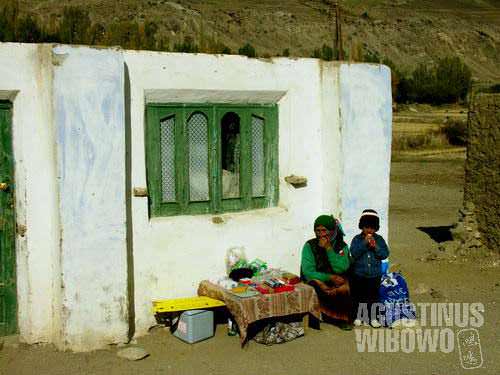

The peaceful village of Ishkashim

Life in Ishkashim was peaceful now. “There were lots of tension in GBAO, between each ethnic group: Shegnon, Wakhani, and even Pamiri. People were hungry and the war brought more tension,” Alisher observed about the life during the civil war. He also reminded me the fact that there were more Tajiks crossed the border to Afghanistan during the war here, and not the other way round. It was Pamir Relief, one of Aga Khan’s organizations, which brought the food to the isolated GBAO during its difficult time. When the situation was improved, Pamir Relief changed its name to be MSDSP, an NGO to support the development in Tajikistan’s GBAO (now extended to Tajikistan’s two other provinces). Some interesting projects of the NGO included introducing alternative non-agricultural production to the villages. This was remarkable as people in Tajikistan’s GBAO usually had less land and animals compared to their brothers in Afghanistan side. The MSDSP also tried hard to build cooperation with the government of Tajikistan for the development of the rural area, but according to Alisher, not much that the government had done to GBAO as they thought that most works had been and should be done by the Aga Khan Foundation.

Aga Khan played very important role in the life of GBAO. He delivered speech during the Civil War of Tajikistan about the importance to save this isolated province by its own government. Aga Khan also made diplomacy with the Uzbek government when there were rumors that Uzbeksitan would use the chance to attack Tajikistan. A Russian juournalist, said Alisher, criticized the intervention of Aga Khan thorough a biased writing named something like “The Dangerous Game in Central Asia”. Nevertheless, in the eyes of all Ismailis, His Highness Aga Khan was always a big saviour.

It had been peace time in GBAO now. The food aid programme from Aga Khan Foundation had been much reduced and people had to start to rely on themselves. Tajikstan was hardly beaten by the oil price, which brought the inflation of all things. Alisher’s old mother was surprised to know that sugar now cost 3 Somoni per kilo. Luckily for most of the daily food, like potatoes, wheat, tomatoes, was sufficient from their own garden. People from the villages were luckier because they still had land which supplied them their daily need. Income never improved though and unemployment rate was high for ever. Jamshed, an unemployed boy from Ishkashim, told me that the unemployed still received money from the government, 30 Somoni per month. Jamshed had just finished his military service, compulsory for all men for 2 years. The 30 Somoni per month ‘unemployed wage’ might be compensation for the military service, which he considered as time wasting activity in the middle of nowhere (his duty station was in Karakol Lake).

The people of Ishkashim were nevertheless very educated. They read a lot and watched TV for news and documentary programs. Two of Alisher’s uncles were asking me about the relation between Island of Sarandeep and Indonesia.

“Is Sarandeep really Indonesia?” asked them.

I know not how to answer. I had never heard about that.

Alisher explained, there was an ancient Persian historian who mentioned Sarndeep as 12,000 islands where the first men came. Sarandeep was also mentioned in the great epic Shahnama of Ferdawsi. Sarandeep might be oriented to Indonesia, argued Alisher’s uncle, as it was said the first man’s fosil was found in Java, the Java man (Homo Javanensis and Pithecanthropus Erectus). Thus, Prophet Adam might be a Javanese?

A “shop” in Ishkashim

A night before, the Russian TV broadcast a documentary about Indonesia, and it was about the life of ex-headhunter and cannibals of Batak ethnics in northern Sumatra islands. Alisher uncle recounted perfectly the beautiful lake Toba, the island in the middle of the lake, the beheading platforms, and the giant flowers. I was amazed.

It was interesting to see how the people started their day. The common breakfast in the area was shir choy (milk tea), milk mixed with tea, salt, margarine, and oil. The bread pieces were dipped in. This was a strong breakfast as the ancient warriors went to wars just with this food. I was eating in the Pamiri House part of Alisher’s house on the first day, but on the second day he invited me to eat in the smaller room with his family.

“Now you are not guest anymore. You are part of our family. Welcome!” said him.

The neighborhood in Ishkashim was very warm and friendly. As Alisher was local boy who spent most of his time out of his village, his coming to home attracted his friends and relatives to meet him, greet him, kiss him. It seemed that almost everybody here knew him. Ishkashim reminded me a lot to my home village in Java.

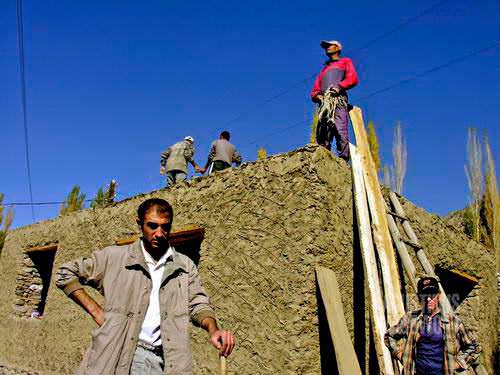

Sunday morning, Alisher’s uncles and cousins came to this house to help Alisher’s father to put roof on his new guest house, a small house built in the garden to specially entertain the guests. Alisher’s father retired already but was still strong and active. The house was made from mud, a mixture between water, sand, and grain, traditionally-made cement. It was a collective work, ‘hishar’, as this work had to be finished by a team work. We also have hishar in Indonesia, and we call it as ‘gotong royong’.

Building house together

I stayed 3 nights in Alisher’s house. On Monday Alisher had to return to Khorog and I continued up (here, as in Afghanistan’s Wakhan Corridor, direction was given as ‘up’ and ‘down’ as altitude play the most important role in the mountainous areas. Heading east from Ishkashim was ‘up’ and west ‘down’). In those three nights, with the hospitality of the family, I felt really at home, as here, ‘feel at home’ phrase was not merely lip’s cosmetics.

Leave a comment