The Jakarta Globe (2011): An Indonesian’s Lust for Asian Travel

An Indonesian’s Lust for Asian Travel

Lisa Siregar | May 26, 2011

http://www.thejakartaglobe.com/lifeandtimes/an-indonesians-lust-for-asian-travel/443364

For Agustinus Wibowo, a travel writer who has explored and lived in some of the most dangerous parts of Central Asia, traveling is all about gaining fresh perspectives — even if it means going unshowered for months or getting kicked out of an Afghan man’s house for refusing the generous offer of a male prostitute.

“It’s not about the number of stamps in your passport. It’s the traveler’s point of view that matters,” he said last week during the launch of his new travel book, “Garis Batas” (“Borderlines”).

He showed up to the launch proudly wearing a white flowing tunic known as a shalwar kameez from Afghanistan, where he had lived for several years.

Agustinus, now a translator based in Beijing, is famed for his travel columns published in Kompas newspaper as well as his first book, “Selimut Debu” (“Blanket of Dust”), published in January last year.

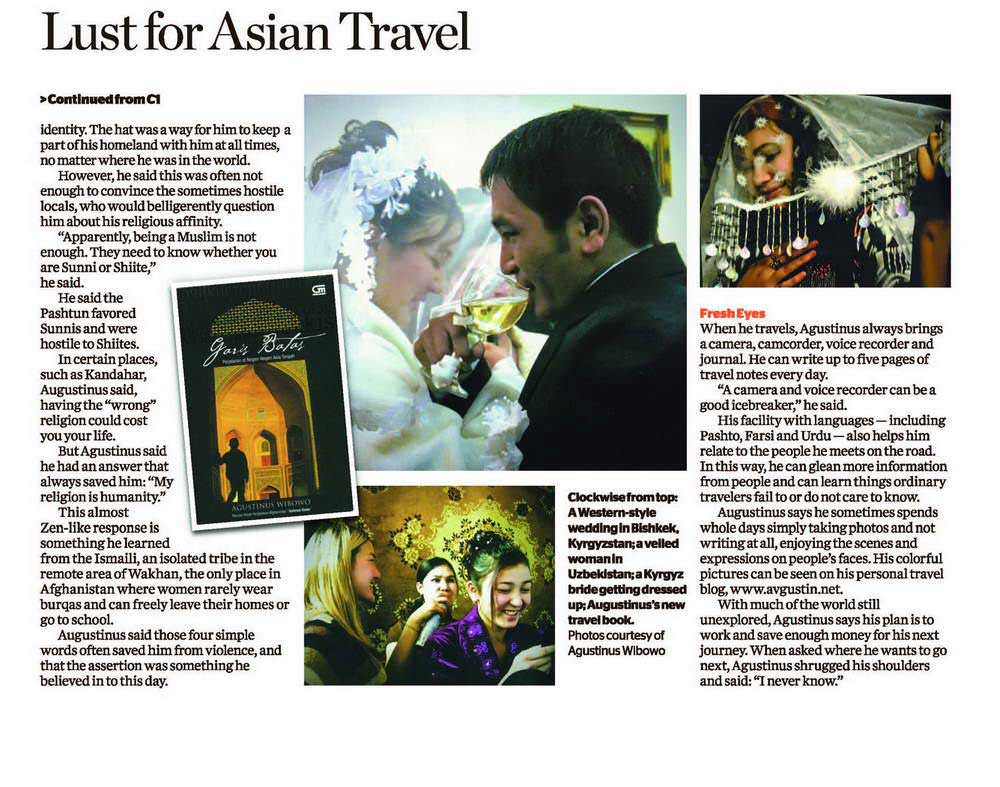

Most people like holidays in luxurious, or at the very least comfortable, spots. Agustinus is a bit more adventurous. His new book, for example, details his sometimes nightmarish experiences in Tajikistan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan.

Once, his things were stolen in an attack dubbed “vodka terrorism,” the Kazakh term for when drunken locals rob hapless travelers. He did not shower for two months while living with a nomadic tribe in Pamir, Afghanistan. Another time, he was kicked out by his Afghan host because he turned down an offer of a bacha bazi, or a young male prostitute.

Not Your Typical Trip

Agustinus, born in Lumajang, East Java, caught the travel bug when he went to Beijing to study computer engineering.

At the beginning of his journey, his goal was to travel through Asia and end up in South Africa, because it was “the farthest point one can go from Beijing without taking a ship or plane.”

“At first, I had the typical backpacker ambition to conquer the world,” he said.

But his original plan took longer and longer to accomplish after he was “gripped” by the sights he saw along the way. While traveling through Pakistan, he finally got a visa to Afghanistan in 2003 and found himself unable to resist the pull of the conflict-torn nation — even if this took him further away from South Africa.

He was strangely excited by Afghanistan’s dangers after the United States-led war.

Back then, he was still an inexperienced backpacker. When he arrived, Agustinus said he found the country rather peaceful, compared to his second visit in 2006.

He had initially planned to spend four months sightseeing on his second trip to the country, but ended up getting a job as a photojournalist in Kabul, the Afghan capital, where he lived for two years. Over time, he said, the sight of the horrible devastation wrought by bombs became a normal sight.

“In 2008, even suicide bombings did not shock people anymore,” Agustinus said. “They happened so often that Afghans would casually joke about human heads in the markets being cheaper than animal heads.”

Although his books touch upon the many traumatic experiences from his travels, they also highlight the kindness and hospitality of people from various cultures.

He discusses at length how countless people helped him throughout his journey, such as the kind tea-shop owners who let him spend the night for free. When public transportation drivers demanded exorbitant fares, locals would often intercede and help him negotiate a fair price.

It is precisely the kindness of strangers and the generally warm welcome he receives as a guest in a foreign land that keeps him coming back.

An Indonesian Perspective

Agustinus’s books are uniquely compelling because they offer an Indonesian perspective on war, hegemony and identity. “As an Indonesian, I know how it feels to be a citizen from a nation that was born out of colonialism and adores nationalism,” he said.

Indeed, his writings often reflect on the nature of citizenship and how arbitrary borders and identities are.

Human struggles, he says, inspire him to travel and write. “Selimut Debu” described Afghanistan as a country covered in a blanket of dust and ruined by war, yet filled with minority groups and tribes filled with the desire to live and survive.

In his latest work, Agustinus details the Central Asian countries’ struggle to find a national identity in the post-Soviet Union era.

“I have learned that not all nations dream of independence and democracy,” he said.

Agustinus, who is Buddhist, also had his brushes with sectarian conflict. He had to hide his religious affiliation during his years in Afghanistan.

The Indonesian Embassy in Kabul advised him to pretend to be Sunni while in Kandahar, the birthplace of the Taliban, for safety reasons. Due to his looks, Agustinus said he was often suspected to be a member of the Hazara, a longtime enemy of Kandahar’s Pashtun people.

Although he took care to don a Pashtun-style shalwar kameez, he never forgot to wear a peci to display his Indonesian identity. The hat was a way for him to keep a part of his homeland with him at all times, no matter where he was in the world.

However, he said this was often not enough to convince the sometimes hostile locals, who would belligerently question him about his religious affinity.

“Apparently, being a Muslim is not enough. They need to know whether you are Sunni or Shiite,” he said.

He said the Pashtun favored Sunnis and were hostile to Shiites.

In certain places, such as Kandahar, Agustinus said, having the “wrong” religion could cost you your life.

But Agustinus said he had an answer that always saved him: “My religion is humanity.”

This almost Zen-like response is something he learned from the Ismaili, an isolated tribe in the remote area of Wakhan, the only place in Afghanistan where women rarely wear burqas and can freely leave their homes or go to school.

Augustinus said those four simple words often saved him from violence, and that the assertion was something he believed in to this day.

Fresh Eyes

When he travels, Agustinus always brings a camera, camcorder, voice recorder and journal. He can write up to five pages of travel notes every day.

“A camera and voice recorder can be a good icebreaker,” he said.

His facility with languages — including Pashto, Farsi and Urdu — also helps him relate to the people he meets on the road. In this way, he can glean more information from people and can learn things ordinary travelers fail to or do not care to know.

Agustinus says he sometimes spends whole days simply taking photos and not writing at all, enjoying the scenes and expressions on people’s faces. His colorful pictures can be seen on his personal travel blog, www.avgustin.net.

With much of the world still unexplored, Agustinus says his plan is to work and save enough money for his next journey. When asked where he wants to go next, Agustinus shrugged his shoulders and said: “I never know.”

Leave a comment