Tokmok – The Dungan

“Хуэйзу либянди щинфу” – Happiness Among the Dungan

Hueimin Bo 26.01.2006

My first interaction with the Dungans was with its food. There is a busy, crowded, small restaurant near the Iranian embassy in Bishkek offering Dungan food. When I entered the underground room, I felt I was thrown again to China. It is Chinese, and only Chinese language, spoken among the cook and servants. The food also resembles Chinese food you eat in mainland China, with slight variation of Central Asia touch. That second I immediately decide: I want to know who the Dungans are.

Tokmok is a little town 70 km east of Bishkek. This town is located nearby to Chuy River which now separates Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan. Tokmok is a kaleidoscope of ethnics: Kyrgyz, Kazakh, Uzbek, Russian, Uyghur, and Dungan traders stuff its busy Sunday bazaar. Tokmok is home of most Kyrgyzstan’s Dungan population.

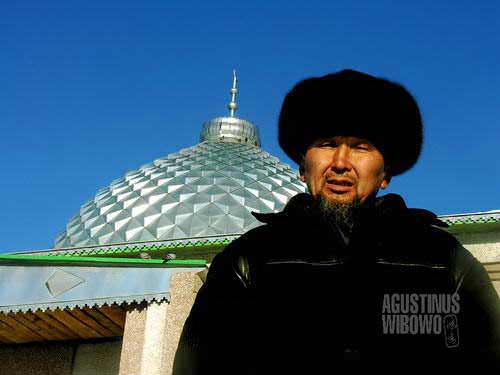

Not far from the bazaar there is a little Dungan mosque. Here, in Central Asia, as countries are split into ethnic-nation idea (e.g. Kyrgyzstan – the country of the Kyrgyz, Uzbekistan – the country of the Uzbeks, etc) even the mosques are now ethnic-based. The Dungans only go to their own mosque and never visit the Kyrgyz mosque near the Tokmok bus stop. Only occasionally Muslims from other ethnic groups visit the mosques not set for their own ethnic. For sure ethnic group separation is not in Islam. The existence of ethnic mosques like this show a certain degree of ethnic identity in Central Asia emphasized since the definition of ethnics in the area in Stalin time.

But Dungans are in anyway different from the Kyrgyz.

Kemal, 32, is an unemployed Dungan man who spends most of his time around the bazaar in his friend’s workshop, a shoemaker, near the Dungan mosque. It was the first time I communicate in Dungan language, or what they call as Hueizuhua, simply a northwestern dialect of Mandarin Chinese. Kemal’s Dungan language is not really good and he actually better expresses himself in Russian. But Dungan is his native language, and he uses it in his daily conversation.

“I don’t have even passport and ID card,” says Kemal.

“He actually lost it,” correct the shoemaker.

“It was very, very easy to get passport and ID card before,” continues Kemal, “the Kyrgyz government was very generous. Now not anymore. I still don’t have documentation and whith my local Tokmok permit I only can travel at most 60 km away from Tokmok. To the west at most I can go to Bishkek. That is exactly 60 km. To the east I can only reach the tip of Issyk Kul. That’s now all of my world,” he continues sighing.

The localized permit, which limit the travel of a country’s own citizen, is a remnant of the socialist years under the soviet union.

Kemal says, Inshallah, this year, he will get a national passport which then allow him to travel anywhere in Kyrgyzstan, but still prevents him traveling abroad.

Because I came almost dark, the shoemaker offers me to stay in the mosque. At fist they think about letting me to stay in local rest house, but considering the general safety in Tokmok and especially now as they regard me as ‘guest’, they say mosque is the best option.

Lao Han, the old caretaker of the mosque, stays in a tiny room behind the temple. Kemal prepares for me cold rice, which then he puts on the heater to make it warmer. Meanwhile, I take the tea and bread while the other men performing the dawn prayer, Maghrib – the fourth prayer in a day. I tell them I am not a Muslim yet so I don’t go to pray with them. After the prayer, the men come again to the room to warm their body, as it is only in the Lou Han’s room that one can find such a nice warm temperature in this freezing winter.

It is not more that two small cups of tea, then the Isya time – the fifth prayer for the Muslims, come. The men rush again to the mosque to perform the final prayer of that day.

The men, not more than 8 people – not an optimistic number in a country where most people claim to be Muslim, consist of two young boys and some elder men from 30 to 60 years old. Lao Han seems to be the oldest among all, as his long white beard and silver hair testify his age. The young boys don’t speak much Dungan language, and it seems that Russian has replaced the language in their tongue.

The imam, who dresses in a Central Asian coat and wear a Turban during prayers time and comes back to a fur cap after it, is also not very old. He asks me why I didn’t perform prayer as I am too old already to keep being a non Muslim. I just tell him, maybe the time has not come yet.

It was a quiet night after. One by one the men leave the mosque. Only Lao Han and I left. He doesn’t talk so much. He does what a traditional Chinese would do: sleep early, wake up early. Be fore the sun rises, at 6, he already starts the Morning Prayer. He is the muezzin, the prayer caller. He sings beautiful azan – the prayer call, and it was quiet loud without the loudspeaker. I wonder how many people come to the mosque at this early morning time. But I indeed don’t have the material to be a good Muslim – I just couldn’t leave my bed before the sun really rises.

As there are not many Muslims in Kyrgyzstan perform the complete prayers as requested by the religion, the number of people who bother to rush to a community mosque to perform prayer at this such inconvenient time of the day might be very depressing.

Anyway, Lao Han in many sense reminds me to a traditional Chinese Buddhist monk in a temple like Shaolin. His attitude, his obedience, his solemn, … but he holds different identities now: as a Muslim as well as a Chinese.

I learn more about the Dungan from Ali, 60, a respected man from the village which Kerim introduce to me. Kerim says Ali speak very good Chinese so I can talk anything with him. Ali’s original name was Ma Jingsheng, and unlike the younger Kerim, he was educated in China until quite a high level that he master the language quite properly. Ali and a group of people from Yining crossed the border to Soviet Union in 1962. He was in the first grade of high school (chuzhong) at that time. The border post was Khorgos, now is a Kazakhstan-Chinese international border.

This is one among several waves of Dungan migration to the Soviet Union. The first migration was about 120 years ago after the failed Dungan uprising against the Qing dynasty. In 1932 the border saw reserved migration where many Dungans crossed from the Soviet Union back to China, due to the Stalin repression to the wealthy people in the Soviet Union. Ali’s parents were among these people.

These people, in spite they were Chinese, were called as Sukiao (Overseas Soviets) in China. The term ‘Sukiao’ is comparable to ‘Huakiao’, the overseas Chinese who live anywhere outside China. As a descendant of Sukiao, Ali had got the priority to go back to Soviet Union in 1962 when the border opened again to welcome the migration of the minorities from China. Actually the border was opened earlier, between 1950 and 1958, and passports were not needed to cross, but migration was restricted to the Sukiaos. Most of Tokmok Dungan population had a history with the year 1962. Not only the Sukiao crossed from Yining and Yili, but also other Muslim Chinese, Uyghurs, Kazakh, and other ethnic minorities. Some were legal, others were not.

The Dungan never call themselves as Dungan. Their original name is Hueizu, ‘huei’ in Chinese means ‘return’, and ‘zu’ is ethnic. Their religion, Islam, is also called as ‘hueikiao’, possibly because it is the religion of the Hueizu. Any Dungan may well describe the history of their ‘Huezu’ but mostly unaware why they are called as ‘Dungan’.

Ali doesn’t know either how the name Dungan came upon their heands.

A friend of him, who welcomed the return back of his compatriots from China, asked, “Do you know why you are now called as Dungan?”

“No,” Ali answered.

“It is because you are chased from the east and now come to the west. Cong dongbian gan dao xibian lai le!” explained his friend. Dungan, is then, an acronym of Dong (east) and Gan (chase).

Of course, this is merely a joke.

Any Dungan will refer themselves as mixed blood of Arabs and Chinese. Dungan means the children of Arab father and Chinese mother. “Our father,” said Ali, “is from Arab. That is our religion, Islam. Our mother, our language, is Chinese.” This ethnic philosophy dates further in the history.

The Dungans were the Chinese who were converted to Islam about 800 years ago. Ali recounted there were Arab invaders to their land in interior China, behind the majestic mountain ranges of Tienshan and Pamir. The king was frightened by the Arabs and he then presented his princess to be married by the Arab to prevent the unwanted war. The descendants of this mixed marriage are the today Dungans.

Part history, part myth, that’s how the Dungans consider Arabs as their father and Chinese as their mother.

Then the Arab invaders and traders decided to settle down in the area of present-day China. This is how the Turkish language name of the Dungans, Turghani, came. ‘Turghani’ in Turkish means ‘settle down’.

The Chinese name Hueizu is an irony then. Why the people who chose to settle down then called as ‘returning people’, as what ‘Hueizu’ literraly means in Chinese? Ali said ‘Huei’ actually is an acronym of ‘Hueibuliao’, ‘cannot return’. These Arab descendants then settled in China for thousand of years, forming one of present day Chinese 56 minorities, the Hui ethnic. The trace of Arab blood is now not strong anymore among the Hui as now they have similar physical appearance with the Chinese majority Han.

The Dungans in Central Asia comes from several entry points. Khorgos in Kazakhstan border and Karakol in Kyrgyzstan border were among the most popular entry points. There were mosques with curious Chinese architectures in both of Khorgos and Karakol, but there are not many Dungans there anymore. Among the visible remnants of Dungans in Kyrgyzstan’s eastern border at the shore of the giant lake of Issyk Kul are maybe the variety of the distinctive Chinese (Dungan) food, like ganfan (Dungan rice) and tofu.

Why there are no more dungan community in Karakol? The Kyrgyz who now use the Chinese mosque said that they disliked the Dungans and chased them away westward. The Dungans say that the life around the lake didn’t suit them.

Nowadays the Dungan community in Kazakhstan concentrated in Karakungus (Masanjin), Shortube, and Zaravostok in Almaty. There are also Dungan concentrations in Kyrgyzstan in Tokmok, Alexandrovka, Ivanovka, Milyanfon (curiously still preserve its Chinese name – Miliangfang), Kanbelu, Kantt, etc. All of these small towns are scattered nearby the Chuy river. Even in Tokmok, Dungan is not the majority. There are only some thousands of Dungan and most of them stay in the town center.

The Dungans have their unique life which now differs them from the Huizu counterpart in China. They don’t celebrate anymore the Spring Festival, or the Chinese New Year. They don’t read Chinese characters and instead they read and write Cyrillic Chinese, comparable to Pinyin Romanization used in Mainland China. There is Dungan school in Tokmok where children also study their language, but now it’s more important to speak Russian, and to some extent, Kyrgyz. The Cyrillic Dungan script eliminates the tones, which are very important part of Chinese language, causing understanding a text is extremely tricky. The proficiency of Dungan language (hueizuhua) is very low among the youngsters. There is tend of deterioration of the language from a generation to a younger one. It is not uncommon to hear Chinese language conversation to be popped-up with Russian or Kyrgyz words, like “hazer we lai (now I am coming, ‘hazer’ is Kyrgyz for ‘now’)”, or ‘saat wu (five o’clock, ‘saat’ is Kyrgyz for ‘time’)

The deterioration of the language is balanced by the stronger identity as ‘good’ Muslims. Lerim tells me that Dungan is the real Muslims, while those ‘black-children’ are not. The Dungans call the Kazakh and Kyrgyz as ‘heiwazi’, literary black doll, black baby, or black children. They also have curious nicknames for the Russian (er-maozi, or maozi) and Cyrillic (maozihua, the language of Maozi). “Those black children like to drink very much. They also eat pork,” says Kerim. This is one among the reasons the Dungans dislike, or look down, the locals.

Lao Han referred Kyrgyzstan as ‘zeigue’, the country of thieves, due to rampant corruption of the officers who harassed the people frequently. Corruption is not something new here, as well as ethnic tensions. One among the cases happened on 24 March 2006 when there was fighting between the local Kyrgyz and Dungans which caused damages to houses and vehicles. The army had to stop the fighting by pistol firing.

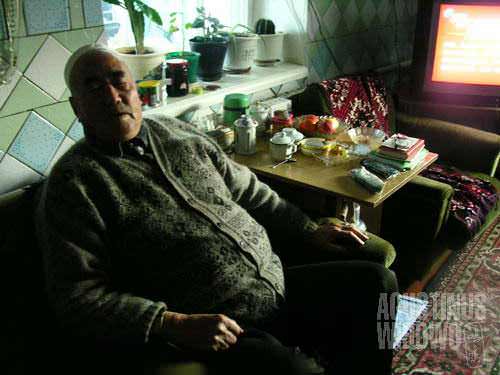

Yeja Kerim keeps up to date with Chinese Communist Party activities from the China Central Television (CCTV) in his house

Yeja Kerim, one of the most respected men in the town, thinks the other way. He insists that there is no discrimination by the Kyrgyz government towards the Dungan minority. In fact the treatment is now much better compared to USSR time when Soviet relation with China was chilling. Now after the independence of the new republics, everything gets better. I notice on their passports there are two entries worth to mention: place of birth and ethnicity. The Dungans who were born in China, no matter whether he is Sukiao or Hoakiao, have it written ‘Kitai’ (China). For everybody, the ethnicity is written as ‘Dungan’. How these passport entries affect the live of the Dungans? Yeja Karim said none. Everybody is the same, no matter what ethnicity or place of birth the passport says.

Yeja Karim has experienced the important phases of Dungan history. He was born in the Soviet Union. When he was a child, he followed his parents, together with other wealthy people, to migrate to China to avoid Stalin socialist programs in 1930. He was raised in China, as a Sukiao. In 1954 he was even a teacher in a school in Yicheng, Yili, Xinjiang province. This is the reason that his Chinese language is perfect.

On 14 September 1961, Yeja Karim chose to go back to Soviet Union, when the country opened its gate to its former citizens. Yeja Karim was among those Sukiaos who crossed from Khorgos to Kazakhstan. He was a Sukiao in China, and now he is a Hoakiao in Kyrgyzstan.

The identity issues always become questions and being questioned to the foreign diaspora minorities.

The earliest history of the Huakiao in the Soviet Union actually started a century back. In 1868 there was a Hui uprising in Yunnan against the corrupt Qing dynasty. The Qing successfully defeated the revolt in 1888 and since then there were waves of Huizu refugees (then to be Dungan) from China to the steppes west of the mountains. Yeja Karim’s parents were among these people, and that is why he was born in Kazakhstan.

The name ‘Dungan’, said Yeja Karim, also came by accident. The refugees didn’t speak any Russian and the Russian border guards didn’t speak Chinese either. When the refugees were asked their place of origin, they answered, “Dungfang Kansu lai (from Gansu in the east).”

Then all of the Hui refugees were called as Dunggan, no matter whether they really came from Gansu or other provinces in China.

Being Dungan is both being Muslim and Chinese. Yeja Karim has performed hajj pilgrimage to Mecca, something that is still a luxury for Muslim counterparts in China due to the government restriction. But in another side, his Chinese identity was also strong. He has a satellite TV and when I visited him, he was in deep concentration watching Fujian TV news program broadcasting 100 names of the local communist party’s new comrades. He is proud to be a Chinese, and feels sorry that the new Dungan generation now cannot even read any single Chinese character. He loves China but at the same time he doesn’t dislike the Kyrgyz.

“Everywhere in the world is the same. Everywhere is home (quan shijie shi yimou yiyang, daochu shi yijia),” said him, then continued by singing a Chinese communist march. He is proud of Chinese recent rapid development in all sectors of live. “China is getting stronger, Huimin (dungan) and Chinese descendants also will be stronger.” The position of Huizu in China is also stronger, as one of the recent vice presidents is a Hui ethnic.

The past, for Yeja Karim, is as important as today and tomorrow. He has a huge collection of Chinese philosophical literature, as well as the Holy Koran in Arabic script (the Kyrgyz local only read it in Cyrillic).

Muhammad, 50, is among the people who perform the daily prayers in the local Dungan mosque. He lives with his wife, old mother, son, daughter-in-law, and some grandchildren. His family is undoubtedly quite prosperous one, as they posses some cars. His wife performed hajj in the 1970’s, overland from Kazakhstan to Mecca, through Iran, Syria, and Iraq, where she learnt too much about life as Muslim. She was indeed surprised that now Iranian girls wear tight jeans, make up, and smaller black chador. “Life has changed,” sighed her.

Muhammad’s old mother, Fatime, was still performing prayers at the corner of the room when I came. She speaks only Chinese. Muhammad speaks some Russian to his son and daughter-in-law and also to the grandchildren. Chinese now is reduced to only simple conversations in the family.

Chopsticks, still show the mental relation of the Dungan to their homeland in China. The Uyghur laghman, dumplings, and Chinese sour pickles also present on daily basis on the dinner table.

During the evening, Muhammad gave me a scrap of Dungan language newspaper, published in Kazakhstan. “Study this, so your Hui language will improve!” said him to me.

I examined the full Cyrillic newspaper. It is interesting to see how the complicated Chinese hieroglyph now reduced to lines of Russian characters. The tones are neglected makes it very confusing to read and to understand. As the Dungans came from western China, the western Chinese dialect variation of Mandarin Chinese now is fixedly shown by the Cyrillic spelling, like the inability of the people to determine ‘n’ and ‘ng’ sounds, ‘f’ from ‘h’, ‘n’ from ‘l’, or the Mandarin diphthongs which then often reduced to monophthong in Dungan.

It might be also interesting for the Chinese speakers to guess what this following Dungan text (originally in Cyrillic) means. The title is ‘Hueizu Libyandi Tshingfu’ or ‘Happiness among the Dungan’, taken from Hueiminbo 25 January 2006.

Gi Nimundi fujyazyshon : Hueizu Libyandi Tshingfu

Almaty chenni tshinjin na vurus hua ba Khazakhstan hueimin tshehuidi fuzuntun, jyoiutshuedi kandidat Mariya Nabievna Vansvanovadi “Hueizugue li dei tshyanzeidi Jeze” (Hueizu Dungane – Proshloe I Nashtoyatshnyeye) fuyin chulei li…

Hei Wazi is not Black Sock. Wa Zi means baby, or boy, a dialect by northwestern China