Maimana – Bacchabazi

“Playboy is good” – Massoud

The public vehicle going to Maimana from Mazhar e Sharif departed as early as 4 a.m. Traveling in Afghanistan is painful. Road lights don’t exist at all so that traveling should be only done during the daylight. Road to Maimana starts to deteriotae at Shibargan, when the road turned into Dasht-i-Laili desert. I took a Town Ace, 500 Af, which is 100 Af more expensive than the crowded Falancoach. But the extra money was really worth for the comfort. The Town Ace only takes 8 passengers while Falancoach 18, and the road in the desert is not a nice roller coaster trip in a jammed minibus. The distance between Maimana and Mazhar e Sharif is merely 341 km, but it took 10 hours to reach.

When arriving in Maimana, the driver tried to extort money from me. I gave 1000 Afs then he said, “sahih shod, everything is allright.” Instead of giving me 500 Af bill, he gave me much filthy smaller money, and when I counted, it was only 400 Af. I got angry, asked my money back. He gave me the right change. Then it was turn of him getting angry, “Get off!!!” screamed him.

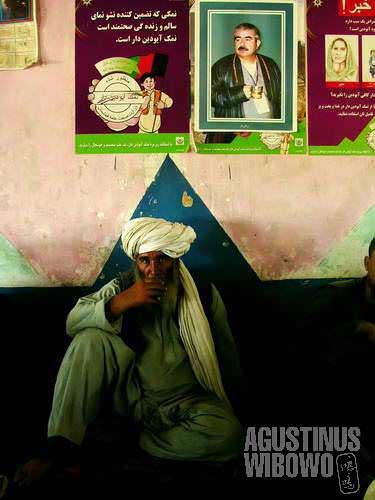

Before arriving in Maimana, we stopped for lunch in Daulatabad. The town looked like wrapped in history, along with the dust from the desert. The people in this province, Faryab province, are predominantly Uzbeks. The old men were still wearing huge turbans and had interesting beards. Everybody was still wearing the traditional dress, some with the stripped zebra Uzbek cloaks. In the restaurant, the atmosphere was more like in the past, despite the arrival of TV which grabbed attention of all visitors. The tea to be poured from the pot where words were exchanged from the mouths surrounded by beard under the turbans of the old men sitting on the floor. Thy whole air was filled by the smog produced by the kebab fire.

Dasht e Laili is a dry desert. It’s still providing life to the cattle of the herdsmen. Hundreds of sheep were herded by the family, and many of them lived in tents and yurts. It was dry yellow scene. I wonder how the animals here eat, despite the lack of water and grass, but they still look fat.

The public transport of the villagers to go to Maimana was a very old truck, filled by lots of cattle and sheep skin that the only space left for the passengers was the roof. Motorcycles also existed but still the major transport of everybody was the efficient and obedient (depends on the personality and psychological characteristics also) donkeys.

I found Maimana, the capital of Fayab province, was not much different. Except here there were more concrete bazaars and shops, a row of paved roads, a dry park, mobile signal (only Roushan), and horse charts as public transport. If in Daulatabad I saw almost no women at all, as the rough desert life might be more suitable for men, in Maimana with more bazaar city atmosphere, women were more visible, though most of all were in burqas. Young girls now started to wear jeans with black jacket and black hejab, resembled the fashion style of Iran.

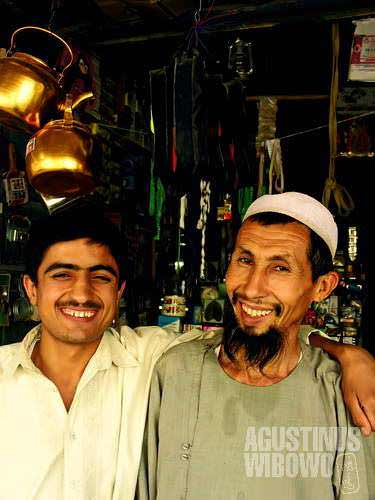

There were a row of shops, selling everything, mostly rugs and textiles, along the bazaar road. One of the owners spoke very good Russian, as he spent 6 years in Ukraine. He said he was the only one speaking Russian in the area. Children and men were so excited to see foreigner, very, very rare here as almost no tourists make their way to Maimana. Every shopkeeper asked me to be photographed, some even were ready to pay me money. Life is simple, people are simple.

But Massoud might be the most sophisticated guy in Maimana. He has a shop selling mobile phones and he boasted he had 20 shops in his young age of 18 (I thought he should be around 21). He wore clean beautiful white Afghan dress. He offered me to stay in house, which I didn’t refuse, as he said, “I like you very much.”

Sitting in front of his shop with other two young friends of him, we had afternoon chit chat. He introduced his friends as ‘brothers’, later I found it was merely ‘Muslim brothers’, not blood bothers. They speak good English, and one guys spoke Urdu also as they spent some years in Pakistan as refugees. Masoud spent his whole life in Afghanistan.

“Today there was a big demonstration,” said Massoud, “it was political and I cannot tell you now.” I kept asking. Massoud promised to tell me when it’s safe. When his friends left, Massoud started to recount about the demonstration in Maimana, which he was just joined. It involved 2000 people, claimed him, and even BBC reporters came here. The demonstration was against the government, protesting the Karzai regime not giving General Rashid Dostum any proper job. Dostum now lives in Shibergan. For me the case was interesting. Dostum was once a big warlord during the Mujaheddin and Taliban time, ruling the northwestern areas of Afghanistan, which is dominated by Uzbeks. For many Uzbeks, Dostum, despite of his cruelty and no possession of education, was the hero of the ethnic. Massoud said Dostum was terrorist and robber, but he still went to the demonstration to support Dostum. To give a political position for such a big figure like Dustum, but even cannot read and write except to play Kalashnikov, is a dilemma for Karzai. For the Uzbeks, it was not the matter. The matter was how they to be represented in today Afghanistan.

Later on I found, even Massoud (his name coincided the great Afghan hero from Tajik ethnic, Ahmad Shah Massoud) is not a random boy from the street. His house is extremely big. I saw only the guestroom and it was as big as an office, with some sofas and furniture. He might be one of the richest families in the area, as he said that his uncle was governor in an neighboring province. I bet his father was also an important government officer, but he didn’t want to tell me. As the family is loyal government supporters, it was strange why Massoud when down to the demonstration to support the old Dostum and anti Karzai. I bet the most probable reason was about fun, for a boy of 18 as he claimed, crowds could be a real fun in the sleepy dusty days of Maimana.

When he walked on the street, he always looked left and right, just like when one crossing the crazy roads of Surabaya. But Maimana is not Surabaya, the traffic is more of the animals and we were walking on pedestrian way. I knew he was afraid of spies. He had himself bodyguards, hidden every where in the corners of the town to give him full protection and information. He is indeed not a normal boy.

“Dostum is not normal. He likes to kill, to rob, and to fuck boys,” said Massoud. To fuck boys? Massoud it was the culture. The term in Farsi is bacchabazi. Baccha means boy and bazi means ‘game’ or ‘to play’. Thus abbazi (swimming) weans ‘water game’, and ‘baccha bazi’ means ‘to play boy’. That is also the reason why some Afghans refered ‘male-to-male actions’ as ‘playboy’ when they speak English.

“Bacchabazi is Uzbek culture,” said Massoud. It was bizarre. He was the first guy I met who proudly declared gay sex as part of his proud culture. “Do you think it’s good?” asked him to me. “Well, every ethnic has their own culture. And as outsider I have no enough right to determine good and bad,” I answered diplomatically. “What do you think, it’s good or bad?” I asked him. “It’s good. I like playboy very much,” Massoud answered, “in Maimana it’s very easy to find boys, and in Faryab province it’s really full of them.” He even used the word ‘all’, giving impression all Faryab men were playboys.

“So where do you play the boys?”

“Here!” said him pointing the room where I was, only together with him.

“When do you do?”

“At day, at night, nobody comes here. I have bodyguards outside, it’s very safe.”

When I asked him how many guys he had played with, he said hundreds. I pointed the number was surreal. Then he reduced to 40.

“You give money to the boys?”

“Sometimes. Sometimes some boys ask, ‘give me money’, so I give them some money. It’s only 100 Af.” Boys are cheap in Afghanistan.

“I only fuck, they ‘give’ to me,” said Massoud about his sexual desire, “I never ‘give’”.

And at the end, after the delicious Kabuli rice dinner, he looked at me, “Will you ‘give’ me?”

“NO!”

I managed to sleep that night untouched as I had to depart from Maimana the morning after at 4 a.m. and I was very tired. There was something happened during the night, which I’m really sorry that I can’t tell you here in this occassion, but surely it was scary. Fortunately Massoud didn’t try further to force me.

I was reminded to the sentence he said to me when we met for the first time, “I like you very much.”

Manly traditions isnt it