Chisht-o-Sharif – The Journey through the Central Route

“Where in Afghanistan Indonesia is?” – a passenger from Obey

My today had nothing to do with the remembrance of the September 11 accident. So was the life in this part of Afghanistan. Everything was just the same as it was in any other days. I started my journey to Kabul through the Central Route of Afghanistan, passing through the mountainous areas from Herat, Ghor, and Bamiyan provinces.

I had heard that the bus to Obey, the first stop of the Central Route, departed from Darb-e-Khosh near the Friday Mosque. When I was there, there was no car at all. There was another old villager with big sack like that of Santa Claus, as confused as I was. After asking around, we found that we were waiting at the wrong place. The old man told me that we should take a rickshaw to the bus terminal. There was a mini bus going to Obey, 2 and half hours away from Herat. The ticket was 90 Af. The old man was still thinking I was a Hazara from Ghor province, as I told him before I was going to Chekhcheran, the provincial capital of Ghor.

“Kojai asti? Where you from?”

“Indonezia,” I answered.

“Hazara asti? Are you Hazara?”

“Na, Indoneziai astam, No, I am Indonesian.”

“Afghanistan, Andonezia kojast? Where in Afghanistan Indonesia is?”

Villagers travelling on the truck in Afghanistan western provinces. The central route of Afghanistan connecting Herat to Kabul is unpaved for about 900 km. Public transport is extremely difficult and villagers rely on hitchhiking trucks to travel around.

I was wearing Afghan traditional dress with vest and shawl, and my Mongoloid appearance even ceased the locals. Being Hazara looking in central route, thus being a local, was a good opportunity.

The old man was a farmer from Obey, went to the bazaar of Herat for selling products. He was poor, but very friendly. At the end of the journey in Obey, he was still unaware that I was a foreigner. He helped me to find the connecting transport to Chisht-o-Sharif.

The road to Obey, as that further until Kabul, was unpaved dusty path. But the road inside the little town of Obey was, surprisingly, smoothly paved. The pavement of the road was just recently, following the economic flourish of Herat. Villages in the districts of the province also demanded further development. On September 10, 2006 there was a small demonstration in Herat in front of the government office. Villagers from a district nearby came to the city to urge the government to build road to their village. People in this province enjoyed much rapid development compared to those in other provinces, let’s say, Faryab, Badghis, Badakhshan, and Ghor, where demonstration asking development of road to the villages would mean nothing, as even the provincial capital had no road nor electricity.

The ruin of a mausoleum in Chisht-o-Sharif. Chisht-o-Sharif is one of Afghan numerous historical sites, as well as a pilgrimage site. The mausoleum of Chishti, the holy man who introduced Islam as far as India, is located in this village.

Chisht-o-Sharif was further 2 hours by shared taxi (150 Af) from Obey. The little village is an important pilgrimage site as the holy man, Chishti was born here and introduced Islam to as far as India. There are ruins of two old buildings, presumably were medressas, at the entrance of the town.

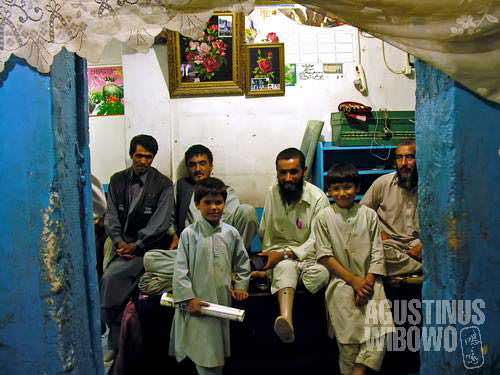

The bazaar of Chisht itself was sleepy, quiet bazaar. Iqbal, an old man who had a hotel-restaurant (samovar) famous in the village was proud of his restaurant’s meat rice. It was indeed nice, as plain white rice was uncommon in Afghanistan where they prefer to prepare rice with sauce. The meat was also very delicious. Iqbal was, though, a funny old man, asked me to photograph him around different corners of his samovar with different poses.

Chisht was supposed to flourish further with development of a dam nearby. The project was conducted by Indian government. I met the Indian engineer, IBrahim, from Kerala. He didn’t speak Farsi but he had a Pakistani Pashtun translator to translate his Hindi command to Farsi. The Afghan workers were also now busy of learning Urdu (the national language of Pakistan, very close to Hindi) in order to be able to communicate with the Indian boses.

Transport further east was difficult. Falan coaches and even trucks were very rare these two days. I spent two nights in Iqbal’s samovar before being able to continue my journey, waiting for lift.

Leave a comment