Garmao – The Minaret of Jam

“What was illegal has to be legal now, but what is legal is still illegal.” – Mohammad Yousuf

Nassir Ahmad, a driver from Heart, owned a Mazda truck. His Mazda served as a public transport to the villages along the Central Route of Afghanistan, especially for those in Heart and Ghor provinces. From Garmao, some traders from the Jam village hired his car to transport their trading goods, and Nassir offered me a ride to the historical minaret of Jam.

We departed from Garmao at 5:30 in the morning, delayed an hour from the initial planned time. Garmao, literally means ‘hot water’, seemed got its name in mistake, as the morning was extremely freezing. The truck had been loaded by goods of the traders, from rice, wheat, until strawberry jam and carbonated drinks Zam Zam from Iran. We, the hitch-hikers, sat on the open truck on the trading goods. The wind was very strong, and chilled.

The rugged hills of Ghour province. Transport in this province is difficult and its isolation prevents this province, which has played an important role in Afghan history, from further development.

Jam is located 10 km away from Garmao. There are two routes from Garmao to the provincial capital, Chekhcheran. The north route, which passes through Jam, is much less traversed than the southern one, due to the difficult high passes with steep angles. The Mazda simply couldn’t climb the passes. Half of the goods in Nassir’s vehicle had to be unloaded before climbing a steep hill, then the small truck might climb up till the pass slowly. The other half of the goods had to be unloaded, the truck went down the hill to load the first half of the goods, and climbed the hill again to load the second half ones.

It was not an easy job.

But Nassir Ahmad earned his living this way. And people like him were desperately needed in transport-difficult villages like Garmao and Jam.

The village of Jam was extremely green, resembled a fruit garden. The girls and women didn’t cover their face. They wore beautifully embroidered, colourful skirts and trousers. Some women had burkas, and even the blue burkas were beautifully embroidered with golden thread. The women didn’t use the burqa to cover their face. As in Chihst-e-Sharif, girls of 6 years old, or even less, had already started to wear burka. When they don’t wear burka, they wear hejab shawl topped with a cap, a fashion that I only saw in this area. Even the donkeys in this village had beautifully embroidered saddles.

Compared to the women, girls, and donkeys, the men dressed much simpler. Just the common Afghan traditional dress with turban or cap.

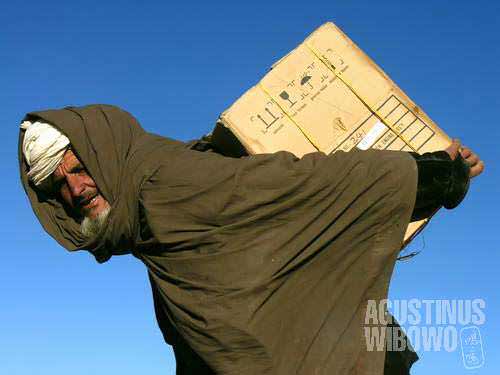

A villager with box of the material he is going to sell in the village of Jam. Jam has no market and all daily needs are brought from the Herat province.

The village of Jam consisted of several shops along the unpaved main road. The houses of the people were made of mud and surrounded by muddy walls. The schools were just three tents provided by UNICEF.

“I like the government of Mohammad Daud. He had done much for the people,” said Nassir, 30 years old, remembering the glorious days of Afghanistan. The communist government of Najib was not bad either, much development had been done. But he didn’t like the king Zahir Shah, whom he considered as ‘homeland seller’.

The history of Afghanistan, rise and fall of the country, was very clear in Nassir’s mind. He said that in our life there is time of being up, and there is always time to fall down. His left leg had to be amputated due to a mine he stepped on 10 years ago. “I don’t know it was Russian mine or Taliban one.” I didn’t notice that he was using a fake leg, as he walked normally and as a driver, he navigated his truck on the difficult mountainous track beautifully. If he had not showed his plastic leg, which now had been part of his body, I wouldn’t have notice that he was one of Afghan war victims.

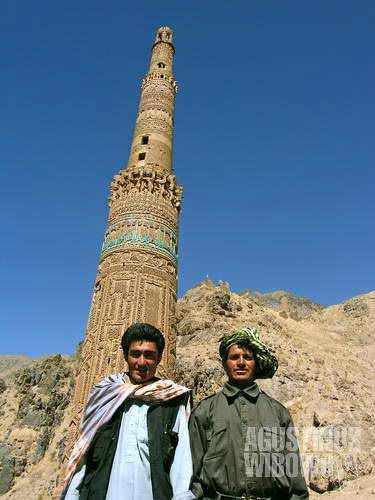

But history of Afghanistan was not only about wars. The glorious past of the Ghaznavid dynasties can be seen from the beautiful minaret of Jam, hidden among lonely mountains in such unreachable area. The minaret is 5 km away from the village, approached through river beds of Hari Rud, and the 65 m tall minaret, suddenly, miraculously, appeared from between the hills. It was a shocking scene.

Why such a grand architectural work had to be built in such isolated area? Until now historians hadn’t found the answer yet, even though some theories had been proposed. This second highest minaret in the world, of which design had influenced th architecture of the world’s highest minaret – Qutb Minar in Delhi, might be a mark of a pre-Islamic holy site. This 800 year old minaret now still stood proudly, preserved, mostly due to its isolation. The grand minaret was exposed to the outside world less than 40 years ago, and now, in hard currency desperate country of Afghanistan, the monument was also expected to earn some income. The ticket imposed to foreign visitors was 5 dollars, another 10$ for car parking, another 10$ for climbing up the minaret, and a hotel cost 30$ per night was built by UNESCO, became the only choice of accommodation in the area. When I visited the minaret, nobody was there collecting the ticket. Maybe the man in duty was too much bored of waiting for tourists to come.

Nassir, who took me to the bottom of the minaret together with his 8-year-old sister, Farooh, took me back to Garmao. I decided to spend only a few hours in the monument area, as transport was really difficult and waiting for the next ride might take days.

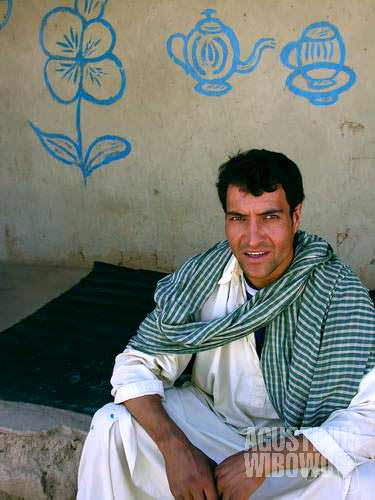

Back to Garmao, I met Mohammad Yousuf, an old man in his sixties with his pure white beard. Yousouf spent his 50 years working in Iran, and now was waiting for a ride to take him to Herat to get a visa. He came from village further than Jam, and walked for 8 hours to reach Garmao to find the onward transport. In the Central Route of Afghanistan, transport was not at all reliable on the unpaved, broken, muddy road leading to nowhere, and one might wait for days to get a vehicle.

“When it was Najib government, I was fighting against the government. I was a Mujahid (freedom fighter). I also went to Iran for work. I had 25,000 Af and I started my business there.” He entered Iran illegally from the border in Zaranj, and walked, literally walking, to Mashhad. The hiking took him weeks. He asked me, “who is then the world traveler, me or you?” rhetorically. But it was his past time adventure. Now he had to apply for visa to go to Iran. “What was illegal has to be legal now, but what is legal is still actually illegal. To get the legal way by passport, the government price is 800-900 Af, but they will make us waiting for months, in four times visiting the office. But if we have money, say, 25000 Af, we can get the passport in one week.”

Yousuf was illiterate. He asked me to see whether his Iran visa was still valid. It was expired. And it was only a single entry visa. He was so desperate to go to Iran despite of his dislike to the inhospitable people there. Life in this part of Afghanistan was too difficult. The mice attacked the gardens and fields in the villages, brought failure to fruit production. Wheat and rice had also to be bought from outside. “We don’t have tractor, what can we produce?”

There was no electricity and transport was so rare. He regretted that his home was in the isolated Ghor province, rather than, for example, Chisht-o-Sharif in the Herat province. “Otherwise I could go to the Iranian consulate easily,” explained him why.

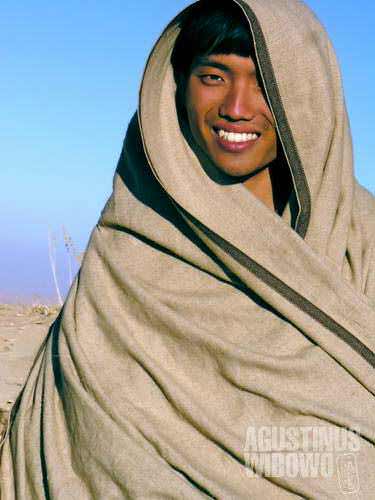

Yousuf was such a kind man, as any other people in this poor neighborhood. He even gave me his blanket (kampal) to cover my body when I was sleeping on floor of a dirty restaurant (samovar). He was not rich at all. The food from the simple samovar even was out of his budget. He brought 5 boiled eggs from their family chickens and just ordered tea and bread (nan) from the samovar. It was just 15 Af. Nevertheless, due to his hospitality, he still insisted me to take one of his eggs. One thing that I wouldn’t never forget about him, he never stopped citing, “Afghanistan, zindagi kheyli moshkel.” (life is so difficult in Afghanistan)

Due to failed harvest, people in the area were more desperate of living. The herdsmen had to sell the cattle to Herat more often. In normal condition, they used to sell 50-60 sheep (800-2500 Af each, depend on the size) to bazaar in the provincial capital of Herat twice a year. But now some people had to do it about once in a month, in smaller quantity each dispatch. Truck service offered by drivers like Nassir Ahmad helped these villagers a lot. But it also cost a lot, about 5000 Af one way. Anyhow, nan and tea had to be prepared everyday from the dark kitchens.

Leave a comment