Noraseri – Living on Faith

In deeply religious Pakistan, it is important to pay attention to their culture and religion so not to offend them

March 25, 2006

Islamic Republic of Pakistan, a country which was founded to house the Muslims of India and to establish a country following the way suggested by the religion, was among the most famous countries in Muslim world. From a discussion with a Pakistani scholar, it was stated that the founding of Pakistan was not only to guarantee the freedom of religion (as people were also free to pray in India), but also to guarantee the life in God’s preferred path.

What was the meaning of the name of Pakistan? Formally, Pakistan means land of pure. Some other people claimed that the name of the country referred to the essence of Pakistan: Punjab, Afghan, Kashmir, Sindhi, and Balluchistan (Bangladesh, the ex East Pakistan, didn’t find its place in the name of the country). Another man in Muzaffarabad told me that the meaning of Pakistan was Laillahaillallah, the holy kalimah of Muslims, which means there is no god but Allah. No matter what, the name of the country had already inferred the hope of being the ones preferred by God.

Iman, or faith, was the most essential part in the religion. There are some basic faiths, faith to God, faith to the prophets, faith to the Holy Koran, faith to the doomsday. Faith doesn’t allow the question whether God exist or not, as if you have the faith, you believe that God is there. I was asked for many times about the concept of Buddhism about God. But in Buddhism we never query whether God is there or not, as it was not the essence. This kind of answer always aroused in debates, which then I preferred to answer, “I don’t know”, rather than being involved in emotional fruitless debates.

The faith was the answer of every question. Even though I was raised in a Muslim society, the belief to faith in Pakistan was still astonishing. That day I was discussing with a cook about the habit of Pakistani people to share the same glass in restaurants. In India they did also drink from a water pot or a common glass in restaurants, but they didn’t touch the pot or the glass with their mouth. In Pakistan, it was not a problem. You may drink from the common glass, as it was your own glass. I asked the cook whether there was no disease can be transmitted this way.

He then told me a story; a British scientist gave his hand to be salivated by a dog. Then he put much soap to clean the hand, rubbing hard, and washing hard. He put his hand after washing under microscope. He saw many bacteria still existed on his hand. He did the hard work of washing again, and again. But his hand was never clean. A Muslim mullah then did the same; his hand was salivated by the dog. He didn’t wash. He just read some prayers, spat on his hand, made it dry. Then his hand was also examined under the microscope. And, miracle happened. There was not even a single bacterium on his hand. Then the British became a Muslim. But the moral of the story was, you would not get sick or infected by others if you were eating with Muslims. The story was told to me by a Pathan from the NWFP province, the place with the strongest and most traditional belief in the country.

This not only about sharing plates or cups, but also including not washing hands before eating. I noticed many people directly eat the roti bread (the most common staple food in Pakistan, and understandably, was commonly eaten by bare right hand) after the work in the field. I didn’t know whether it was laziness of washing the hands, lack of water, or just merely the belief that they wouldn’t get sick.

In villages in Java, Indonesia, many answers of the prohibitions was returned back to unknown reason, sometimes mystical. In Java, parents told their children not to sit on pillow, otherwise there would be pimples on the butt. Parents also told the children not to walk around while eating; otherwise the legs would be fat. But many of the times, the parents also didn’t know how to answer, and they used the mythical word of “ndak ilok”, sin, taboo. My mother used to say that three people should not be pictured together on a photo. I asked why. She just said, “ndak ilok”. The term “ndak ilok” was not merely a taboo, but also contain frightened that bad luck would come if the taboo was not followed. And this term was mythical and powerful.

In Pakistan, many of the questions were returned to the religion. A guy told me not to drink while standing, then busy of bringing me a chair and asked me to sit down. I asked why. He asked it was gunna (sin), a religious cause. Another day I saw a boy brushing his teeth with eucalyptus stick (very common in India and Pakistan). I asked why not using toothbrush. He said that brushing teeth with wood sticks were preferred by the Prophet, it was Sunnah, as Prophet also brushed the teeth with the stick. I thought that it was surprising to try to imitate the Prophet’s life as to the detail of the toothbrush, as the Prophet lived a thousand years ago and there might be no toothbrush at that time. But the belief was the answer. I also learned that having beard and wearing sarong were another Sunnahs, because the Prophet also had beard and wore sarong.

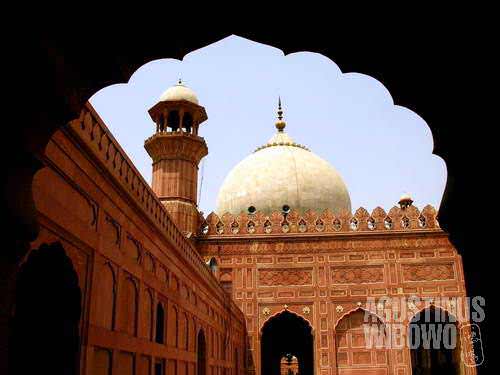

The prayers, five time a day, is one of the most important pillars of Islam. The prayer calls in most parts of Pakistan were usually delivered by loudspeakers from the mosques, same as in Indonesia. This was true to most of Pakistan, except in Hunza and Gojal where the people were mostly Ismaili or Aga Khani, whom the Muslims here judged as Non-Muslims. In Hunza, according to Ismaili understanding, the prayer is personal communication between a man and God, the proclamation and announcement is not needed. Outside Hunza and Gojal, prayer calls was comparable with those of Indonesia, with lesser extent. But the listeners of the calls should do the respect. I was in Lahore, in an Internet Cafe, when the owner of the cafe turned off the music when a prayer call came. No singing was allowed when you are listening to a prayer call (azan). Chatting was OK though. Here in Kashmir, I was told by some boys to stop reading my book when a prayer call came. I bet I had offended the people when I was reading, even soundlessly and motionlessly, and alone in my room.

That was the faith, the belief, which answered everything. It was a rainy day, and I discussed about family planning with a primary school teacher in Noraseri. I asked about education in Pakistan concerning about the family planning education. I thought as a teacher, he might have some methods to make the people understand about the importance of having small families. But out of my expectance, he told me that family planning was the scheme of western countries to deal with bigger and bigger Muslim population. I gave the reasons that in Indonesia our educators taught us that we needed small families for better quality of food, education, and health of the children, that the quality was more important than quantity, as now everything also got more expensive.

“Expensive? There is no word expensive for your children,” the teacher said.

“But we do need money to raise the children.”

He then gave me an example. See, the jackals in the mountains, they don’t have money, but Allah feed them, and they are still alive. See the trees in the forests. They don’t worry about their life because they were protected by Allah. If Allah can feed the jackals and trees, why we should worry that Allah cannot feed us?

I argued, we were not animals. We need good quality of food.

He said that Allah stated that when you ate your dinner you should not worry about your tomorrow. Allah would feed the children. And it was also stated in Holy Book that women with many children would find their place in Heaven.

The discussion was turning to be about belief. I tried to turn it back to family planning.

I said that the development of a country should be balanced between spiritual and material, and family planning was not merely a material. He said he didn’t care about material world, because the most important thing is the life after death. The reason was our life now is short, very short. But our life after death would be long. For how long? Nobody knows. But it should be very long.

So, the material development, like good quality of food and education, was nothing to him. About family planning, for sure that, despite his position as an educator, he was against the program, which he suspected as Western scheme to control the number of Muslims.

Leave a comment