Whiteboard Journal (2011): Interview with Agustinus Wibowo

http://whiteboardjournal.com/features/roundtable/interview-with-agustinus-wibowo.html

http://whiteboardjournal.com/old/features/roundtable/interview-with-agustinus-wibowo.html

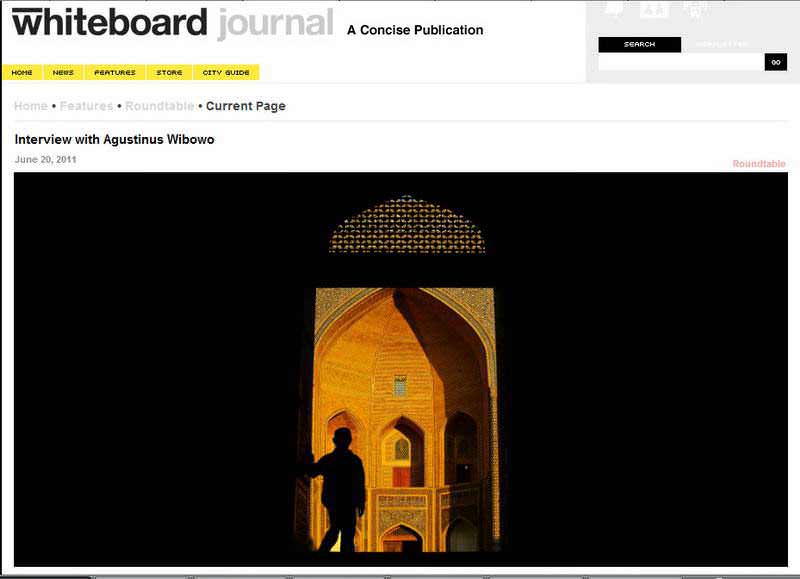

Forming a passion for traveling, Agustinus Wibowo has spent most of his years in a foreign country. Referred as a world backpacker, Agustinus Wibowo whose profession is as a journalist, has taken the road less traveled by going to the depths of China, Mongolia, Afghanistan, India, Pakistan, Iran to the unfamiliar countries of Central Asia.

His contemplative nature and literary adeptness has pushed him to compile his travel stories in a publication called ‘Selimut Debu’ in 2010, and ‘Garis Batas’ recently in 2011.

Whiteboard Journal had a chance to learn more of his purpose of travels and the turnings points that have defined him as a word traveler.

W: How did everything start? What initially drew you to be so engulfed in traveling?

Everything started from childhood, when my dad introduced me to philately. I collected stamps from almost all countries, and stamps were my “window” to the world. I always dreamed to visit the countries of which stamps I have collected. I also loved geography, wanted to learn different languages and cultures. As I was raised in a small town, everything seemed just merely a dream. But then when the chance came, I went to Beijing as a student, and I saw how my fellow students from Japan wandered around the world independently, I just knew the meaning of “backpacker”. I made my first journey in 2002, to Mongolia, where the travel was really adventurous, and that made me really fond of the taste of adventures in travel.

W: Your travel destinations are not conventional to say the least, is there a reason behind your choices of travel?

I started my journey in Mongolia, where in my first and second day consecutively I was robbed and mugged. This experience is kind of near-to-death experience just exactly on my first day of traveling. This made an impression in my mind that the taste of adventures is important. The second year after the trip in Mongolia, I went to Pakistan and Afghanistan, and enjoyed every single step in those countries. But now after traveling for several years, I understand that destination does not really matter. The most important is how your eyes observe and how your heart learns.

W: What do you look for the most in your travels?

In the beginning, I was searching for myself. Until a point that I found, there is no point of searching ourselves, because it’s always together with us. Now when I travel I try to “lose” myself, being totally open to learn what the people, the culture, the history, the world teaches us. From their life experience we can make a reflection of our own life. We can learn from other people’s success and failures and learn from their wisdom. I think this is the meaning of life, because life itself is a journey.

W: Amongst your quest to conquer a new territory, you ended up staying in Afghanistan the longest, what formed this attachment?

I don’t regard travel as “journey to conquer”, it’s not matter of conquer because we as human being is indeed nobody in front of the world. I stayed in Afghanistan because I love the country, the people, and the nature. Afghanistan is like a Pandora box for me. Everything is full of surprise. Of course, there is war and poverty. But besides of that dusty color of Afghanistan, there are so many beautiful colors in the country. And that’s the reason of the love.

W: Your latest publication ‘Garis Batas’ tells about the border that we people set to define our identities (nations, religions, tribes, and so on) for yourself, where do those ‘borders’ lie?

Borders is something to engulf an identity, a difference, something that people can be proud of, and something that people can find their safety zone . In my childhood, I experienced racial discrimination, so the borderlines lied between minority and majority. When I was a student in China, the borderlines lied between the locals (Chinese) and foreigners (including me), which emphasized my Indonesian-ness. When I was living in Pakistan or Afghanistan, the borderlines was between Muslims and non-Muslims. These are just few examples how borderlines can be relative. But after crossing different borderlines, experiencing life at different sides of the borders, the meaning of identity and borderlines itself also changed. Now for me, the universal identity which united all human beings on earth is “humanity”, as we all have something in common as human being, with our dreams and struggles. By having this as our new borderlines, our world would be much wider and universal.

W: Do you think those borders are important? Or would you prefer that we could live as one without these differences?

Yes, borderlines are important, and that’s the nature of human being. With borderlines, we have varied and colorful life. We have diversities and differences, and we have pride. Life without borderlines would be scary, it reminded me to 1984 by George Orwell, where a utopia (or dystopia) means creating a gigantic nation with common enemy, same ideology, same thinking, same values, etc. It’s daunting and inhumane.

Borderlines engulf identity, and identity brings pride. A man without identity, without pride, is a blank man. If I can put it this way, identity and pride is like your financial wealth. You don’t need it all the time, nor need to show it every second, but when you need it, you have it. The point here is, borderlines are always there, but the reality now is how artificial borders (including artificial nationalism, fanaticism, etc) then made a certain group of people feel having the rights to disregard, attack, or even kill others outside their boundaries.

W: After assimilating in different cultures, has this changed your perception of your own country, Indonesia?

Yes, so much. In Indonesia I used to learn that our nation is the most respected country in the world, being praised for its wealth and hospitality of its people. But when I traveled and lived in different countries and cultures, I felt that this claim is arguable. Moreover, I understood the fact that Indonesia is similar to many Asian countries, building our nation and nationalism from the relics of colonization. Our country boundaries were the result of creation of Western powers, thousands miles away. There are many myths created, and we believe them for granted. But, surprisingly some of these myths were very successful to unite Indonesia and becoming our national identity.

W: Are you more aware of where you come from? Or do you feel you have grown a sense of alienation, feelings of both an insider and outsider at your own country?

Insider or outsider is matter of borderlines, and it’s borderlines in mind. For example, I’m from Lumajang, a small town in East Java. When I studied in the province capital, my strong identity was my Lumajang-ness. When I went to Jakarta, it might be my Java-ness or East-Java-ness. When I became an international student, my identity was being an Indonesian. That’s natural, but this was my world view before I traveled. By traveling you would change much of your point of view. Travelers are actually refugees, we are taking refuge from our life and our routine, we try to lose our ego. And when you lose ego, you become nobody, you become easier to adsorb new values, and you will respect differences. I don’t feel differences as a wall which prevents me from blending with people. I might have a different thinking or a different view from other people, but I respect the differences and is eager to learn from the people.

W: With your personal experience, you’ve mentioned in an article, that “not all countries dream of independence and democracy”, would you care to elaborate?

Ex-Soviet Central Asian countries were not expecting the collapse of the USSR, and suddenly they became independent countries, despite of the fact that they were unprepared for the independence. The matter in C.A. was that the countries were artificially created by USSR, so when they got independence, the nationalism, economic, and identity problems became very obvious. All those countries experienced economic difficulties in their first years of independence, while some of the countries are still in a terrible situation. In some countries like Kyrgyzstan, which adopt democracy, the political situation is in turmoil, and recently we saw riots and ethnic clash there. Tajikistan also experienced bloody civil war years just immediately after gaining independence from the USSR. Democracy might be bloody, and citizens are starving. No wonder, I met many people from those countries who are in nostalgia of life under USSR. What’s the meaning of freedom of expression, when you have nothing to eat and when the future is blurred?

W: You also stated that you let go of your attachments of things and people, and have the ability to work anywhere to survive, does living without a sense of having anything to hold on to make life easier?

It’s not matter of easier or not. It’s matter of happiness. When you don’t have much burden or unreachable dreams, you tend to be happier.

W: Thus, what do you prepare for your travels?

I used to prepare nothing, and let every step became adventure. But now the purpose of my travel also changed, it’s a not matter of conquering the world, proving myself, or answering to challenges. But traveling for me now is process of learning. Before visiting a destination, I try to learn their cultures, language, historical background, and look for local contacts that can bring me deeper to their life. I read books, mostly travel narratives and history books about the destination and anything related.

W: What have been both your biggest challenge and most memorable event in traveling?

Biggest challenge is financial. I’m financing all my travels by myself, which means I have to stop many times to earn some money before being able continuing my journey, and sometimes this means I’m stuck for years, for example in Afghanistan, and now in Beijing, China. But I also regard this as the path of my travels, so I also enjoy the struggle. The most memorable was when I got hepatitis in Thar Desert of Pakistan, a local family brought me home and took care of me with full passion for weeks. They were my life savior.

W: Your travel stories are not mere journals; it is packaged in a way that involves elements of history combined with many contemplative thoughts, irony and discovery? Has this always been your thought process?

It developed. When I started my journey in Beijing in 2005, I dreamed to reach South Africa by overland journey. It’s a high target, and kind of putting travel as “conquering a challenge”. But the more I travel, the slower I become. Numbers of countries being visited or numbers of visa in passport became meaningless. I started to learn about life, about culture, and about struggle. And I think that’s the real meaning of traveling, and learning from life.

W: Do you have role models or things that have inspired your travels or writings?

Marco Polo, VS Naipaul (travel writer), Paul Theroux (travel writer), Ryszard Kapuscinski (Polish journalist and writer), and Lam Li (fellow traveler from Malaysia, whom I met several times in Nepal, India, Pakistan, Afghanistan, and now in Beijing)

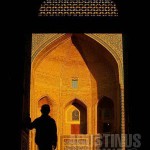

W: Looking at your photographs, you seem to be very in tune with your visual sense, are you a trained photographer? And is there a creative process behind those photographs?

I have never been trained in photography, just the same I have never attended writing class. I learned the techniques by doing. For photography, as I take mostly human interest picture, I understand the power of expression. And to get the natural expression, communication is a must. That’s why I build extensive rapport with subjects before taking their photos, and then follow their daily life to get the most natural photos and to understand their story of life.

W: At the same time, you also have an astonishing ability to master various languages, how do you manage mastering many different languages?

I like languages since I was young. When I was in junior high school, I learned Japanese by myself. Then when I studied in China, I learned Chinese, Russian, Japanese, German and French. Learning several languages made me easier to grab new languages. On the road I learned Urdu/Hindi, Farsi, Mongol, and Turkic languages. I grabbed self-taught books of those languages, and made myself memorizing the basic grammar and vocabulary. Then practice the languages directly in their natural environment. This is an effective way to boost language competence, and also to break the ice with the locals.

W: Where are the next destinations that you would want to explore before finally settling down? And why?

I’m very much attracted by the Middle East culture and dynamics, so I wish to learn Arabic and become a journalist in Middle Eastern countries.

–

Interview by: Athina Ibrahim

Leave a comment