Toktogul – An Old Friend from Toktogul

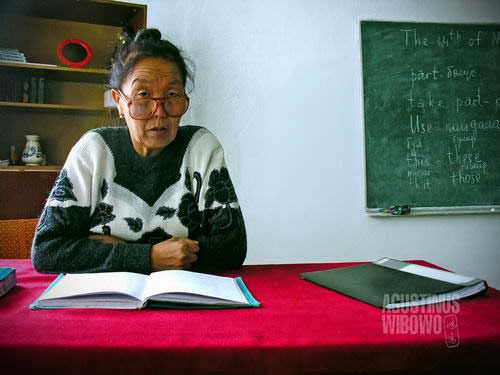

Her name is Manapova Satkynbu, but everybody in Toktogul knows her as Satina or, more properly, Satina Eje (‘eje’ in Kyrgyz means elder sister). She is 53 years old and she is one of the village’s most famous teachers.

I met Satina in my previous visit to Toktogul in 2004 in a very accidental encounter. Satina then invited me to stay in her house, where she stayed together with her only son, Maksat. I spent nice days in the quiet village with the family and two American volunteers, Rosa Bowman and Jason.

This time, after two years and a half passed, I come again as a visiting friend. I arrived in Toktogul after a grueling journey from Osh, in four different public transports.

Life in Toktogul has not change too much. I was lost though, as I completely don’t know any direction here. Today is Sunday and the village is completely deserted. Frustration of life can be observed from Kyrgyz’s most common scene: a drunken old lady lies down on ground next to the main street, after some bottles of vodka. She sleeps like Indian homeless, peacefully. I thought she got heart attack, but she was simply drunk. Not more and not less. It is quiet dangerous to be drunk and faint outdoor like this. Mohammed from Tajikistan once told me about God’s fate; about death which comes at anytime it wants. He told me a story about an old men who went to bar in Russia to get drunk, fainted afterwards, slept on the street in a cold winter and nobody cared of him as it was very normal in Russian society, and found himself already in the tomb the day after. He never woke up. I was afraid this lady in Toktogul who slept in cold weather like this on yellow grass might find the same fate. But one hour later she has disappeared from the spot.

When life is too dull, vodka is an easy way out of frustration.

Due to many failures in Kyrgyzstan after the independence of this tiny republic, vodka consumers increased, criminality (or vodka terrorism) is also on rise. All towns and villages are getting dangerous after dark, and that includes this little Toktogul town. I was warned not to get out of home at night, and avoid as far as possible from the notorious parks. In the other side, Osh harvests its vodka products as being the producer of the best vodka in the country.

By the help of a Kyrgyz boy, Bekbolot, I successfully found Satina’s house. But Satina is not at home. Maksat neither.

“Eje went to the village, she will come back afternoon,” said a girl who keeps the house and says she is Satina’s niece.

She doesn’t let Bekbolot and me in, though. She doesn’t speak English, but Bekbolot translates to me, “I don’t know you. If Satina eje knows I let you in, she will punish me heavily.”

She is right. She is just keeping the house not of her own, and it is better not to bring strangers in easily.

I wait for Satina outside of her wooden apartment.

It is getting dark and cold. Bekbolot says that I can stay in his house as Satina might come very, very late. He leaves his phone number to the girl and asks Satina to call back when she arrives.

Bekbolot is a boy studying in a Turkish college in Jalalabad. The Turkish government built many schools in Central Asia in their policy of gaining support from these new Muslim nations and Turkic speaking brothers. It has achieved a certain degree of success, though. And in Kyrgyzstan, Turkey gains stronger hegemony compared to Saudi Arabia who is trying to export its concept of Wahabism. Kyrgyz young men now speak fluent Turkish and English, as they are educated in Turkish schools, and now are ready to immigrate to Turkey to work. Not sure whether Turkey is ready to give thousands of job opportunity to these fluently-speaking-Turkish Central Asian brothers, as Turkey is still burdened by their own high rate of unemployment.

Bekbolot is originally from Toktogul, but now he comes as a guest. He stays in his auntie’s house. Bekbolot family used to live in Toktogul, but then his parents move to Bishkek. Bekbolot just came from Bishkek by taxi. There was a bus service between Toktogul and Bishkek, but the service is halted since some years a go after a bus full of Uyghur traders from China got an accident when climbing steep pass on the way. Many died.

Bekbolot’s auntie is a merchant in the local bazaar. She has a big house, full of children. The young twin sons just got circumcised. Now the 4-year-old boys run around the house without trousers and showing little ‘elephants’. It seems that they have passed their difficult time.

I also notice that most Kyrgyz prefer to take original Kyrgyz names rather than Islamic or Arabic names. This is a huge contrast to the stronger Muslim ethnics of Uzbeks and Tajiks, of which most people adopt Arabic (Islamic) names. The names of the Kyrgyz come from their long nomadic history, and some most popular names come from Manas epic. A similar comparison is to Indonesian Muslims who adopt Sanskrit names from Hindu epics of Ramayana and Mahabharata. It is not uncommon for Indonesian Muslims to have names like Vishnu, Brahma, Sintha, Larasati, Yudhayana, Bhima, Yudhistira, etc. A friend of mine even is named ‘Muhammad Wisnu’. The first part of his name is the Prophet in Islam, and the latter is one of the greatest Hindu gods, Vishnu. Names, as part of the culture, still survive from the uniformity of the religion.

The next morning I go back to Satina’s house. She is ready going to her school, and exactly at the time she leaves her apartment, she sees me and waves her hand emotionally, “Avgustin!!!!” She laughs happily.

Satina tells me, “I came back very late last night. At 11. I called you many times but the telephone doesn’t work in your place. I worried too much about you. Now I am too happy. Yesterday I was drunk, I drink too much. My niece said I cried the whole night but I can’t remember. Now I am too happy to see you.” Satina prefers to say too in place of very.

Satina says I didn’t change at all since the last two years. Even the neighbors still remembers me. I was the boy with long shorts, for the Kyrgyz it resembled more like skirts rather than trousers. It was the fashion in hot Indonesia but for the people in this village it looks like girls ‘outfit. Now I come back and everybody reminds me about the baggy shorts.

Satina teaches in Birimkulov Elementary and Middle School, the best school in Toktogul. Satina gives me chance to teach English. Satina’s students come from the lowest class until the highest class, and she works together with the US Peace Corps Volunteer, Anna. The classes are divided into two groups, one for Satina and the other for Anna. “My students are stupid,” complains Satina against the passive students. Satina’s students are from the lowest classes and some quiet students from higher classes. When I enter the classroom, the students were all quiet and only speak in Kyrgyz and Satina has to translate everything for me.

Anna students are more active.

“How many brothers and sisters do you have?” asked one young boy from the 4th class.

“How many cars do you have?” asked the other.

“How many apples do you eat everyday?”

Everybody is asking ‘how many’ to me.

The class is studying how to ask ‘how many’. I admire how fast these active students apply the things they have just learned.

In the lower class, that is the class for the 2nd grade students, they don’t speak much English. To make the class livelier, I show the small boys and girls some of my photos from Pakistan and Afghanistan. They are very enthusiastic.

“How many brothers and sisters do you have?” asked one boy.

”I only have one,” I answered.

The class was surprised. “Why not many?”

In Kyrgyzstan most families have big numbers of children. This is a country with only about 5 million population, and it’s encouraged to have more children to have more children. I explain to the children why we have to adopt family planning in Indonesia.

It is simply ridiculous to these students.

“The mothers in Indonesia are poor because the children cannot help to wash the dishes,” a girl with pink ribbon says.

“The father is sad because if his boy goes to school nobody will help him with the animals.”

“If the son is sick then there is nobody to help mother.”

I found the spirit of respect to parents and elderly is very strong in Kyrgyzstan. I also notice this in the public transports in Osh and Bishkek where passengers actively let the seats to the elderly and pregnant mothers. And this is not something created in one night. The mental of respect has been raised since they are very, very young.

Teaching is exhausting. Satina teaches 8 classes on most days. When I finish the classes, I felt I couldn’t say anything more.

Satina’s house is a simple house in wooden apartment of two floors. His husband has died much earlier and now Maksat, his son, doesn’t live together as he is studying in the capital. She is living with her nephew now. She is not rich at all, but she is very hospitable. Every night she cooks special dinner for me. From mantu, pelmen, until shorpa (soup). She also shares the dinner with her neighbor. She also encourages me to practice my Kyrgyz language actively. “You speak Russian very bad. Your pronunciation is funny…,” Satina often corrects my Chinese-accented Russian (I studied Russian in Chinese).

After two years, again I experience the warm atmosphere in Satina’s little house. It is very hard that I have to say good bye to this lovely village. And Satina even has arranged for me the next part of my journey: to stay with Maksat’s stepfather: Moken. Moken is a successful Toktogul man (Kyrgyz: Toktogulduk), working in Bishkek, and owning very beautiful car. Everybody in Toktogul talks about him. Later I found what his job was: a taxi driver.

Leave a comment