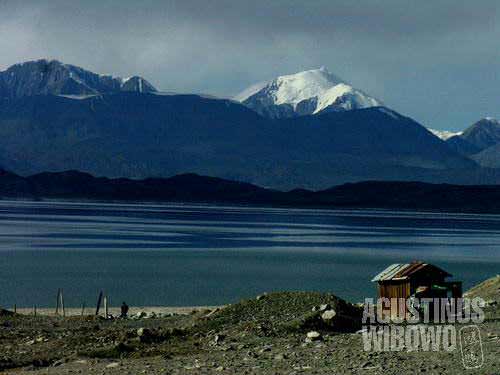

Karakul – the Giant Death Lake

The giant death lake of Kara Kul.

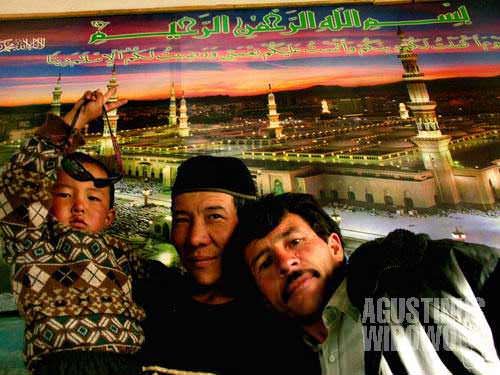

I stayed with a Kyrgyz family, an Acted-arranged guest house. They don’t speak Tajik, but the husband know little bit and can sing the national anthem proudly, “Zindabosh e vatan Tajikistan e azadi man (Long Live o Fatherland, My Free Tajikistan!)” He didn’t understand the meaning of the proud anthem though. Tildahan, the wife, is a young woman, speaks barely no Tajik and had difficulty in determining 30 (‘si’) fro 3 (‘se’). The four year old baby, Nurulek, was an active boy and could smile and shout, “OK! OK!”

Life in Karakul is not that frustrating compared to Murghab. In summer the whole area is green, and water is always plentiful. It is a perfect land for the cattle raising, the way of life which has been the tradition of the Kyrgyz since centuries. Houses in Karakul are sparsely separated. Blocks and blocks of houses along the roads and alleys are loosely distributed. People are not rich, but they are not starving either. Here most families have animals to support their economy. And Karakul water with the green pastureland around it is live support for the whole community. This settlement around Karakul is a new one, just some hundreds meters away from the military checkpoint. I just tried to imagine how the atmosphere was, here, 1400 years ago, when the famous Chinese pilgrim, Tang Xuanzang (the master of the legendary monkey king – Sun Wukong) visited this lake. It might be eerie, mysterious, dead. The fog just flew away from the surface of the death lake when the sun just came in. It was still freezing.

Winter comes very early here in the mountainous Pamir. Karakul settlement has already suffered from the freezing of the water. It has no electricity at all. People can turn on radio still, or tape recorder, which runs on batteries, for entertainment of the boring days. But batteries are not cheap. Television doesn’t run on batteries. Nobody bothers. Local men chose to play chess to kill time, while the women put more wood and coal to the room heater. Other than that, there is not much to do here.

Kyrgyz family of Karakul, with the “OK! OK!” boy

As bored as the people, the border police had to spend years of their ages in this quiet village on mountains. “It is fucking cold here!” said a young soldier from Khojand. This 20 year old Tajik soldier is here to serve his military service (khismat), a two-year-compulsory duty for all Tajik young men. For sure he longed his prosperous town in Khojand (or Leninabad, Tajikistan’s 2nd city) rather than serving in cold isolated village of Kara Kul.

Khursid, the commander of the border guards, is a young Pamiri Tajik man from Khorog. He is only 25 years old, but already earns 300 Somoni (much beyond the national’s average income), and he has 80 soldiers in his troops. I wonder what the 80 soldiers do in this tiny village. “Oh, they do much thing,” said him. The most visible activities are checking all the passing vehicles, examining the documents, and searching for drugs. But do you need 80 soldiers to do that job? The soldiers, almost all of them are in military service – means they were doing all the work for no payment, or at most 1 dollar per month – do many other things. Karakul is located next to the Chinese border neutral zone, and the soldiers have to do patrol along the fences in frosty mornings and freezing nights. The other day I saw a bunch of troop led by Khurshid cleaning the stone road. Most of the soldiers are young Tajiks from outside GBAO area sent here to guard the country. There were some soldiers from Kyrgyz ethnics also, but I saw not more than five.

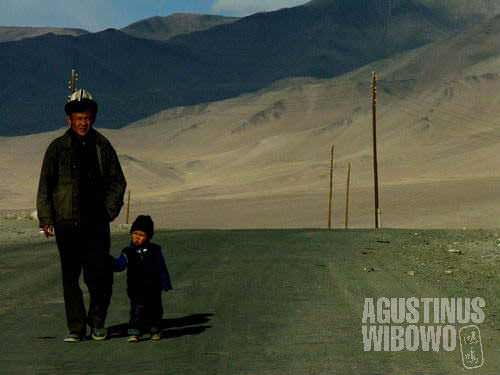

Do you need 80 soldiers here?

Khurshid, the commander, doesn’t speak Kyrgyz language. Most of the time he delivered his command in Tajik language, but also often in Russian. At first he was talking with me very freely, but noticing my over curiosity on Tajikistan military, he then started to suspect me as a spy. I don’t really know why people here are so sensitive about ‘spying’. Maybe they are still nostalgic about their Soviet days when KGB has eyes on anybody, anywhere, and anytime. Khurshid asked my document and it was allright. Then he chose to give me ‘fake information that a spy might need’, like, “see that building? That is where our ammunition is,” or pointing to something resembled a large chimney, “and with that we can deliver a rudal to China!”. The tiny Tajikistan is going to attack its giant neighbor with a rudal from this chimney in rural neighborhood?

Khurshid has a big stomach. He spends most of his time next to the main road, watching the quiet highway. From the place where we are standing, we can see up to 25 km north to Kyrgyzstan direction and 10 km south. In this 35 km stretch of road, there was no vehicle at all. The highway is very quiet. There are about 12 vehicles only per day, says Khurshid.

Bored soldier in quiet Karakul

There is an empty truck stopping in Kara Kul for lunch, heading to Kyrgyzstan. Khurshid asked me whether I wanted to hitch the truck and go to Kyrgyzstan immediately. I still preferred to know more about the soldiers, so I refused. The truck left.

Khursid is now even more suspicious on me, despite of his jovial attitude. He now forbid me to even get close with any of the soldiers. So I spent my whole afternoon just with him and watching sun set on the death lake.

Leave a comment